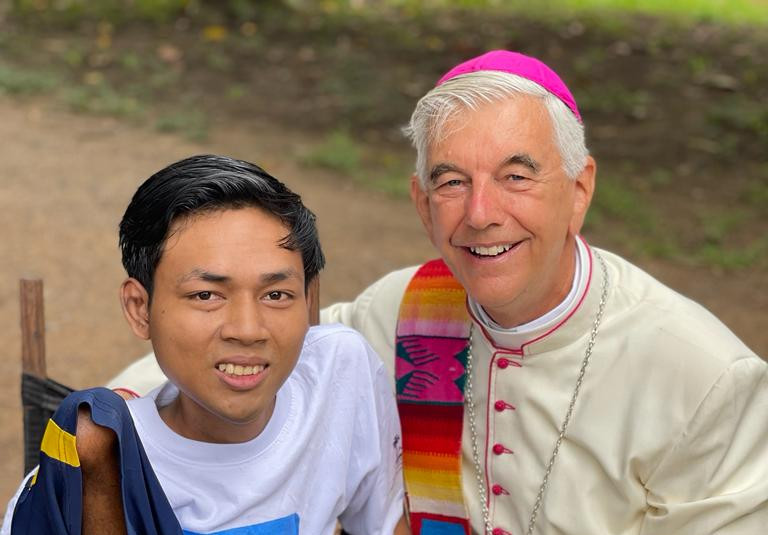

In the lush landscapes of Cambodia, punctuated by ancient temples and rice fields, there exists a poignant narrative of resilience, faith, and transformation. At the heart of this tale stands Jesuit Enrique “Quique” Figaredo, affectionately dubbed the“Bishop of the Wheelchairs.”

His story is not just an account of missionary zeal, but a testament to the profound difference that can be made when faith meets action, particularly when that action is backed by benevolent organizations and the charitable hearts of people worldwide.

Cambodia’s history is marked by both enchantment and pain. The Khmer Rouge era, spanning from 1975 to 1979, saw Pol Pot’s brutal regime devastate a rich cultural tapestry. Left in its wake were emotional scars and the perilous remnants of war: landmines that have maimed countless unsuspecting souls. It was against this backdrop that Bishop Enrique began his missionary odyssey.

“In 1985, I was assigned to work with the Cambodian refugees on the border with Thailand,” he shared, recalling the vivid memories of his time helping personal-mine victims. “I became deeply involved in the lives of the people… and so many things made me fall in love with them.”

Moved by the spirit of service and an undeniable connection with the people, Bishop Enrique was propelled deeper into Cambodia’s heart after finalizing his theological studies in Spain between 1988 and 1992, when he was ordained a priest. This deeper dive was not a solitary endeavor: on the year of his ordination – the Jesuits opened a mission in Cambodia, and efforts to bring wheelchairs to those living in the heart of the country garnered the support of the American Friends Service Committee Organizations.

Speaking of his transformative work, Bishop Enrique highlighted the wheelchair project. “We have workshops run by people with disabilities,” he stated, recounting how collaboration with Motivation International in 1994 gave birth to a wooden wheelchair that became a beacon of hope for many.

“This wheelchair took me to many parts of the country. It transforms the lives of people who move from a dim life, locked in their homes, to being able to study, leave their homes, have a social life,” he said. “But it also transforms the life of the giver.”

“One person once told me that the wheelchair we give is a sacrament, because it transforms people’s lives,” he said. “It is a visible sign of a visible relationship.”

Support the Church in Mission territories

In 1998, when the ongoing remnants of the violence ended, the Vatican’s Dicastery for Evangelization, known for centuries as Propaganda Fidei, which oversees The Pontifical Mission Societies, “was looking for a bishop for the area where I was, and appointed me as Apostolic Prefect. For me it was a huge change, because I was very involved in social work, the integration of the disabled into civil society, and doing outreach … as we so often say now, I was used to a Church that goes out to meet people where they are.”

But the prelate was quick to adapt, and under his leadership, and with constant support from the universal Church, since that in Cambodia is too poor to be self-reliant, the faith has grown exponentially. When he was appointed Apostolic Prefect, his territory had 15 communities, and now there are 31, with 30 new churches built in three decades due to the support of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, one of four pontifical societies. The growth, he said, is an example of what can be achieved when missionaries are equipped with he right resources and the relentless prayers of the global Catholic community.

Today, he still oversees the wheelchair project with a workshop on the side of his church. It employs 18 people, all of whom are amputees from personal andmines, and together, they build an average of 100 chairs a day. During the past three decades, they have given some 30,000 chairs away.

The workshop is primarily self-sustainable thanks to Red Cross International and Handicapped International, which buy 30 percent of the production so Bishop Enrique can give the others for free since the beneficiaries cannot cover the production costs, estimated at $150. “We would like to continue growing because there is a great need still, in Cambodia and so many other places marred by violence, war, and tragedy, but to do that, we would need more capital.”

Bishop Enrique’s philosophy is straightforward and profound: Convey Christ’s message through charity. “Accompanying them, being seen as close and caring, attracts,” he asserts. And it’s evident that his approach has borne fruit, with many drawn towards the faith.

Integral to Bishop Enrique’s persona is his unique pectoral cross, handcrafted in silver by one of the welders in the wheelchairs workshop. It symbolizes his mission and the enduring spirit of the Cambodian people.

“My cross is a mutilated Christ. It represents that Jesus suffers in solidarity with disabled people, but it also tells us that disabled people also suffer with the Lord, completing the salvation of the world,” he said. “And it also speaks to us of the mystical body of Christ, incomplete due to lack of understanding, wars, and not having known the love of the Lord. Our mission is to complete it, with love, understanding, solidarity.”

Read more stories in MISSION Magazine.